One thing that confuses a lot of people—and also happens to be pretty hard to get a good layman’s explanation of on the internet—is what exactly is happening on the House floor day-to-day.

Honestly, the easiest way to get the rhythm of the House is to actually just sit down and watch it, or review the congressional record (which is much more efficient. Once you do that a few times, you will be well-equipped to use the actual useful internet sources.

So I thought I’d walk you through two consecutive days worth of the House floor, the way I often did it each morning at CRS: by actually reading the congressional record. Think of this as a companion piece to my basic explainer on legislative procedure, which you might want to review prior to this walk through.

Walking Through A Day in the House

Let’s start. It’s the morning of February 10, 2026. You crack open yesterday’s congressional record and turn to the proceedings of the House. We can walk through it, letter by letter.

A. The House met at noon and was called to order. Why did the House meet at noon? On the first day of Congress and then again on the first day of the second session of Congress, a resolution (H.Res.6 and H.Res.976, respectively) was agreed to, stating “that unless otherwise ordered, the hour of daily meeting of the House shall be 2 p.m. on Mondays; noon on Tuesdays (or 2 p.m. if no legislative business was conducted on the preceding Monday); noon on Wednesdays and Thursdays; and 9 a.m. on all other days of the week.

But wait, you say, if the resolution says the House meets at 2 p.m. on Mondays, why is it meeting at noon today? Good question! On the first day of the Congress, the House also agreed to a unanimous consent request that, when the House meets pursuant to H.Res.6, it meet two hours early for morning hour debate, one of the various opportunities for Member to talk on the floor unrelated to pending legislative activity. During morning hour debate, Members can speak on the floor for up to five minutes each. No legislative business can take place except for the filing of committee reports. It’s just a chance to talk.

B. The Speaker Pro Tempore was designated. The Speaker is rarely in the chair actually presiding in the House. He’s got better stuff to do than sit there and listen to the debate. Under Rule I, Clause 8(a) of the Rules of the 119th Congress (adopted via H.Res.5 on the first day of the Congress), the Speaker may appoint a Member to perform the duties of the Chair. A rotating cast of Members perform the duty, some of them excellent at the job, others newbies just learning.

C. And that brings us to morning-hour debate. Under the terms of the unanimous-consent request, the parties alternate control of the floor, the opportunity to speak is based on lists submitted by the leadership, and it all has to wrap up no later than 10 minutes before the House is scheduled to be called to order for regular legislative business.

And no, none of the other Members are there listening to this stuff. The House chamber is essentially empty during most debate, and certainly during morning hour non-legislative debate.

And that’s also a key to looking through the record. It may seem like a lot to read, but you can skip all of the substantive debate that you don’t care about. So let’s blow through all of the morning-hour debate, which featured speeches by Rep. Subramanyam (honoring a constituent, talking about a bill of theirs, voicing concerns about the IRS), Rep. Joyce (on the SAVE Act), Rep. Taylor (honoring constituents and various local groups), and Rep. Luttrell (honoring a high school basketball team).

D. At the end of morning hour debate, the hour went into recess. The unanimous consent agreement that structures morning hour requires the chair to use the Rule I, clause 12(a) authority of the Speaker to put the House into a recess “for a short time” at the call of the Chair. Under the agreement, the House is now in recess until the 2 p.m. meeting time for legislative business. At exactly 2 p.m., the Speaker pro tempore (notice it is a different Member now (Mr. Wittman) than it was at the beginning of morning hour (Mr. Smith)) calls the House to order, as required under Rule I, Clause I of the House.

E. The House now proceeds with its regular legislative order. Rule XIV of the Rules of the 119th Congress sets the daily order of business in the House. The only thing that can disrupt this order is privileged business. The first three things in the order—the prayer, the reading and approval of the journal from the previous legislative day, and the pledge of allegiance to the flag—are rarely disrupted. The prayer and the pledge are straightforward, but the snappy approval of the journal seen here is accomplished because no member demands a vote on actually reading and approving the journal. Such demands are very rare.

F. One minute speeches. After the prayer, journal, and pledge, it is unusual for the House to continue along the normal order of business as set forth in Rule XIV. Instead, the House tends to operate by continually interrupting the would-be normal order with either privileged business or by unanimous consent of the House. Here, the Chair has chosen to entertain unanimous consent requests for one-minute speeches. The Speaker has full discretion about entertaining unanimous consent requests in the House, and lays out their policy with regard to them on the opening day of each Congress. In the 119th, as is recent practice, the Speaker allows for one-minute speeches and usually entertains a set number of them at the outset of the day. These are, again, opportunities for Members to speak on any topic, but do not give you the floor for any other purpose. Given that you only get a minute to talk, they can often be wonderfully fiery or humorous.

G. As it turns out here, only one 1-minute was entertained. The Chair then put the House into a Rules I, Clause 12(a) recess at 2:04 p.m., just four minutes after calling the House to order. The recess ended at 3 p.m. Such recesses are used to schedule floor action in the House; it would be known by the Members that the leadership was planning to take up the next set of business at 3 p.m., so everyone could easily plan around it. Note we have a third Speaker Pro Tempore (Mrs. Fischbach) at 3 p.m.

H. The House begins considering suspensions. Absent any privileged business or unanimous consent requests, the House would now continue with its order of business under Rule XIV. That almost never happens. Here we see that Rep. Bice is making a motion to suspend the rules. This is a privileged motion under Rule XV, Clause 1 that can interrupt the normal order of business. It essentially allows Members to ask to do more or less anything without regard to the rules of the House. Most of the time, as is the case here, it is just basic requests to pass bills. Rep. Bice is asking to suspend the rules and pass S.3075, a bill to create a congressional time capsule.

Suspending the rules and passing bills is the most common way for the House to approve legislation. The Chair has total discretion about whether to entertain a motion to suspend the rules—with the caveat that it is only allowed on Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday under the House rules—so the leadership can arrange ahead of time for a set schedule of bills they want to pass via suspension, and they publish a list of bills that will be considered in the House via suspension each week. Once a Member is recognized and moves to suspend the rules, the specific procedures of the suspension motion kick in: a maximum of 40 minutes of debate on the motion/bill, no amendments allowed, and a 2/3 majority required for adoption of the motion.

This last provisions means that suspensions must have bipartisan support. That has traditionally meant they were non-controversial, but in the 118th and 119th Congress we have increasingly seen some use of suspensions on major legislation, as the GOP leadership has needed to cut deals with the Democrats to move appropriations bills and other must-pass legislation. Generally, the leadership will not schedule a bill for suspension unless it is backed by both the chair and ranking member of the committee of jurisdiction.

I. After a brief debate, the motion to suspend was brought to a vote. As is common, no one spoke against suspending the rules and passing S.3075. All allotted time was yielded back by the Members controlling the time, and thus the Chair put the question on suspending the rules and passing the bill. A voice vote was taken, the chair declared that the ayes had prevailed in getting 2/3, and thus the bill was passed. unanimous consent, the available motion to reconsider (which allows anyone who voted for the bill the right to bring the vote back up) was laid on the table, which has the effect of killing the right to reconsider and finalizes the vote.

This is all done very quickly by the chair without much thought. No one is opposed to this legislation, and no one is going to offer a motion to reconsider, so the chair simply states the obvious and moves on. Any Member, however, could object if they wished to retain the right to reconsider the vote on the suspension. In that case, someone would need to actually make a motion to reconsider, another member would make a motion to table the motion to reconsider and the House would need to vote to do so.

Also note that there was no roll-call on the suspension motion. Except where required by the Constitution or House rules, votes in the House are done by voice, and the yeas and nays are only required if demanded by a Member and the threshold set in the Constitution (1/5 of those present) backs the demand. Here, no one demanded the yeas and nays, and so the voice vote carries the day.

The House then proceeded to consider seven other motions to suspend the rules and pass bills, in the exact same manner. We can skip the debate:

On two of these motions to suspend and pass bills, something important happened:

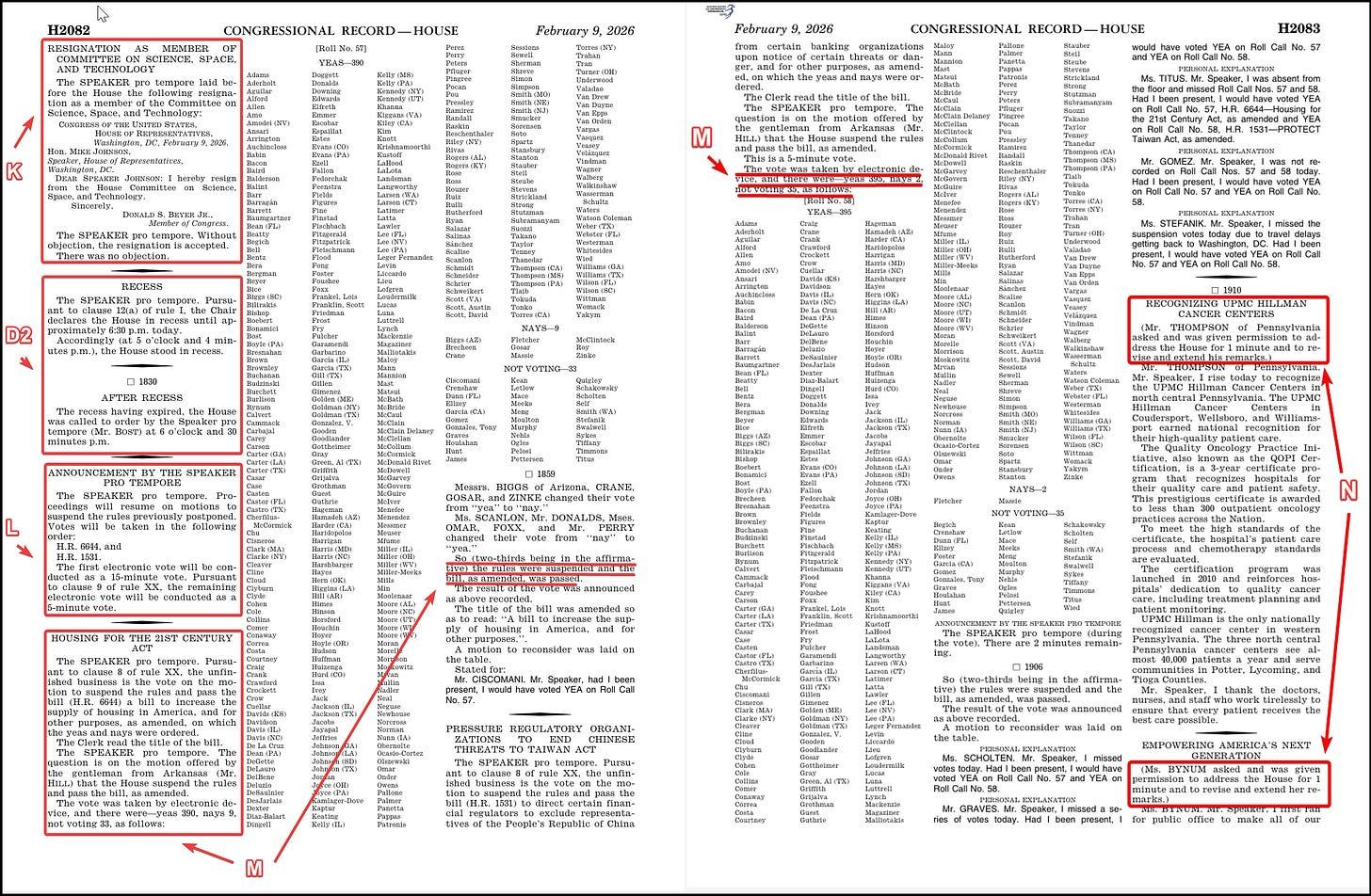

I and J. The yeas and nays were demanded by a Member. On the two motions to suspend and pass H.R. 6644 and H.R. 1531, respectively, a Member demanded the yeas and nays. When this happens, the chair asks those favoring a vote by the yeas and nays to stand up, and if 1/5 of those present stand, the chair orders a record vote. This is all very perfunctory and the chair rarely actually tries to count the 1/5; they almost always just automatically order the record vote.

Note here, however, that they don’t actually take the vote. Instead, the chair uses their authority under Rule XX, clause 8 to postpone the vote. Under the rule, the chair can postpone certain votes for up to two days. Here, the purpose of the postponement is to prevent Members from having to walk back and forth to the House floor constantly; by stacking up all the votes at a convenient and announced time, the Members are freed up to deal with other representative duties without having to worry about being interrupted by floor votes.

K. Processing of Communications. Throughout the day, various communications from the Senate, the president, executive branch agencies, and elsewhere will be received in the House and formally dealt with on the floor, as time permits and the schedule is convenient. Here the Chair is laying before the House a committee resignation by Rep. Beyer, and the resignation is accepted by (implicit) unanimous consent. Routine.

D2. Another recess under Rule I, Clause 12(a). The suspension motions for the day that the chair is going to entertain are complete, and so at 5:04 p.m a recess begins, which goes until 6:30. Why 6:30? Because that is the time that the leadership has previously announced to the Members that the vote stack will be taken on all of the suspension motion that included a demand for the yeas and nays. (See letter D for more on recesses.)

L. Resumption of the Postponed Suspension Motions. After the recess ends and the House is called to order at 6:30 (yet another Speaker Pro Tempore), the chair announces that the proceedings previously postponed under Rule XX will now resume. The record vote will take place via electronic voting. Under the rules of the House, the first vote of any stack must be open for at least 15-minutes, but subsequent votes may be reduced to 5-minutes by the chair at their discretion under Rule XX, clause 9. The chair exercises that discretion, which sets up a 15-minute vote on the motion to suspend the rules and pass H.R. 6644 and a 5-minute vote on the motion to suspend the rules and pass H.R. 1531.

M. The votes are taken on H.R. 6644 and H.R. 1531. As you can see, the vote on H.R. 6644 is 390-8, with 33 people not voting. As that is more than 2/3 in favor, the rules are suspended and the bill is passed. Ditto with H.R. 1531, which is 395-2.

N. The House returns to one-minute speeches. The Chair now exercises their discretion to allow unanimous consent requests for more one-minute speeches. Eleven one-minute speeches are made by Members. It is now 7:10 p.m. and virtually all of the Members have left the chamber for the evening. Legislative business is done for the day. Not technically—the floor is still open for business—but the leadership has made it known that the only thing left that will be entertained is non-legislative debate. That’s just good management practice, and the standard way the floor is run.

N. Special Order speeches commence. Under the announced unanimous consent policies from the first day of Congress, the Speaker will entertain longer so-called special-order speeches under certain policies. These are just like one-minutes, except that you get to speak for up to an hour. You have to sign up with the party leadership, they can’t run past 10 p.m., and there is no more than 4 hours worth of them on any given night. Their genesis is similar to one-minutes—Members want more opportunities to speak on the floor than are available during the normal legislative process.

These things were the bane of the floor staffs’ existence back when there were fewer restrictions and Rep. Gohmert was going the full hour all the time, but now they are much more constrained. Here we see Rep. Clyburn getting 60 minutes for a speech honoring black service members, and then Rep. Haridopolos getting 60 minutes for a speech on affordability, which he shares with a few other Members by yielding them the floor at various points:

Rep. Clyburn uses his full hour. Rep. Haridopolos and friends do not. Right around 9 p.m., the special order speeches end.

O. The House adjourns for the evening. At the end of his special order speech, Rep. Haridopolos moves that the House adjourn. A voice vote is taken and the adjournment is agreed to at 9:01 p.m. Since this is a simple adjournment—rather than an adjournment to a specific time—the House reverts to its previous orders regarding the time of meeting and morning debate, and consequently the House is now set to meet at 10 a.m. on February 10th for morning debate, and 12 p.m. for legislative business.

The remainder of the congressional record is a compilation of actions taken on the floor that aren’t implicated by debate:

This includes: executive communications received by the House, reports filed by committees on legislative items, bills introduced by members, and co-sponsors added to existing legislation.

Wrap Up

I always recommend people who are interested in what is going on in the House do these sorts of walk-throughs. But once you get the feel for the House floor by going through the congressional record like this a few times, it’s much easier to use the daily digest, which includes everything we saw here, but cuts out all of the actual debate.

Coming next: In part II of this two-part series, we will examine what happens on February 10th, when the House takes up legislation via a special order of business reported from the rules committee, the standard way of moving legislation in the House that doesn’t have bipartisan support.